(In September 2024, I added an update at the bottom on my own journey with gender.)

PART 1: How you’re already using pronouns

Check out this sentence:

“Casey called me last night, and Casey said Casey is having a tough time. Casey asked for my help.”

Oof, what a mouthful. That’s where pronouns come in.

Let’s rewrite:

“Casey called me last night, and she said she’s having a tough time. She asked for my help.”

Much better. Except…

“Casey” is one of the most common unisex names in the US, meaning it’s used by people of all genders.

So, in my example sentence, how do we know what kind of Casey we’re talking about?

I could replace “she” with “she/he” or “he or she,” but that’s pretty cumbersome.

Luckily, English already has a solution (we use it all the time).

Let’s say you don’t know my friend Casey.

If I told you that they lost their job recently, you might naturally ask something like:

“Oh no, how are they doing?”

…

Notice what I did there?

I used the pronoun “they” to refer to a single person.

Not only that. I casually used it in the bold sentence above as well to set up the quotation.

Did that strike you as odd? Or simply normal?

Some people object to “they,” saying it only refers to more than one person.

But that’s simply not true. We use it all the time when gender is ambiguous.

If you mention your cousin, I have no idea what gender they are.

Bam, I just casually used “they” again.

(By the way, According to the Oxford English Dictionary, singular “they” actually dates back to 1375.)

Now, here’s an edgy question to ponder (I’d love to hear your response too):

What do we gain or lose by ever using “he” or “she” rather than just referring to everyone as “they“?

(P.S. Notice how I haven’t even mentioned trans or gender nonconforming people yet. We’ll get there, but I hope you can already see that the discussion around pronouns applies to everyone.)

PART 2: Downsides of “he” and “she”

Properly answering the question I posed above is a big undertaking. But I’m going to go through some of my answer in the rest of this post.

Using “he” and “she” boxes us in.

When a human is born and assigned a gender (“he” or “she”), that comes with expectations, possibilities, and limitations.

Based on their assigned gender, they’ll internalize very different stories—about their identity, their place in the world, and what’s available to them.

Those stories will vary based on the culture (and time period).

At the extremes in the US, we might imagine one child in a pink bedroom playing with an Easy-Bake Oven, and another in a blue bedroom playing with G.I. Joes.

This hurts and limits the children in each of those bedrooms in different ways.

Imagine this:

You’re in an online course cohort where everyone is anonymous (no genders listed).

Say you’ve enjoyed regularly interacting with someone, and one day someone who knows them in real life refers to them as “she” or “he.”

What changes in that moment for you? Does it feel like a contraction or an expansion?

Is it pleasant or unpleasant? In what way? (Take a moment and really notice.)

Now, how about this?

Let me tell you about my colleague at work.

“She’s been having a tough time.” (Pause, notice what you imagine.)

Oops, I meant:

“He’s been having a tough time.” (Pause, notice what you imagine.)

Is the type of tough time they’re having different in your mind?

PART 3: The upsides of “she”

Even though I just said “he” and “she” box us in, nuanced topics like this are not either/or—they’re both/and.

So, how is “she” good too?

Women have been marginalized.

Mainstream US culture has always operated under the presumption of two genders (this is what we call the “gender binary”).

This culture has favored men and marginalized women (from a century of fighting for the right to vote, to the glass ceilings & pay disparity of today).

“She” can empower women.

Yes, if we all used the pronoun “they,” we might be boxed in less (i.e., we could each live our lives without culturally-imposed expectations and limitations forced on us when our gender is assigned at birth).

But, using “she” can be a point of pride for women who have succeeded despite the odds stacked against them.

“She” can break down stereotypes. It can inspire young girls to follow their dreams.

There’s power in referring to an engineer as “she”—or any other career that’s typically been dominated by men.

(And, there’s also power in referring to an engineer as “they”—for the exact same reasons, but for people who identify as trans or nonbinary.)

PART 4: The upsides of “he”

In mainstream US culture, guys haven’t had a lot of great role models.

Most men in TV & movies have been portrayed as either:

-

Powerful & overbearing (i.e., toxic masculinity), or

-

Losers needing a strong woman to manage them (i.e., emasculated masculinity).

“He” can help us reclaim healthy manhood.

For those of us who want men to be (and do) better, we can choose to proudly refer to ourselves as “he.”

As a guy into social justice and feminism, it’s been tempting to want to abandon “he.” It feels gross sometimes to be associated with the many toxic men who have used their power to oppress others.

But there’s another option:

We don’t have to abandon the male gender as a lost cause.

We can redefine what’s possible for men. We can retain “he” and reclaim a less toxic version of manhood.

(By the way, I’ve happily noticed more quality “role model” men in media lately. Ted Lasso comes to mind. T’Challa—the Black Panther—is another.)

Bottom line: There are benefits to “he” and “she,” and there are benefits to the singular “they.”

That’s why we each get to choose our pronouns.

That’s why it’s important to share yours and ask someone else for theirs.

That’s why pronoun options are liberating for all of us. (And especially for people who identify as trans or non-binary.)

PART 5: Now, I’ll get more personal.

I’ve covered some of the benefits of “they,” “she,” and “he.”

How has all this affected me?

I began learning about pronouns to be a better ally to people who identify as trans & non-binary.

But along the way, I learned how important this is to all of us.

Gender is a societal construct.

What makes traits “masculine” or “feminine” is dictated by the culture and time period.

Learning about pronouns has informed my own journey around gender identity.

In Western culture, feminine traits tend to include empathy, humility, and slowing down.

Masculine traits tend to include assertiveness, toughness, and being stoic.

If gender is a spectrum with masculine “he” on one end and feminine “she” on the other, I identify a lot more with the traits on the feminine end.

On the other hand, I very much look like a traditional man: my clothing, my hair, my stubble. Plus, I’m not sexually attracted to other guys.

Because of this mix, “they” is appealing to me.

It more accurately describes the combination of feminine and masculine traits I feel inside myself.

And, it’s an act of rebellion—a pushing-back against the status quo that boxes us into only two possibilities.

So why do I still use “he/him” pronouns (for now, at least)?

I’ve gone back and forth on daring to use “they/them” instead, but the big reason I’ve stuck with “he/him” is this:

I want to stay in my lane.

I’m a heterosexual, white, cisgendered guy (i.e., my gender identity largely corresponds with my birth sex).

I’ve gone through life with so many unearned advantages as a man.

Anyone who saw me walk by would 100% refer to me as “he” without a second thought.

That kind of ease isn’t true for many people who identify as trans, non-binary, or gender-nonconforming.

And because many of them appear more ambiguous or outside the norm, they’ve had to deal with a lot of oppression and marginalization.

So, in my view, they deserve to use “they” more than I do, and I don’t want to erase any of their life experience by claiming that pronoun for myself.

Plus, for many people who identify as trans or non-binary, “they” is a much deeper need.

In my case, I’m drawn toward “they” simply because of analytical logic: I like some parts of being feminine and some parts of being masculine.

But for many of them, it’s a far more powerful “felt-sense.” They vehemently feel neither “he” nor “she.”

For example, for some female-presenting people I know (i.e., people who look female), wearing a dress (or highly-feminine accessories) makes their skin crawl.

It’s a strong, visceral reaction, and one that I don’t have wearing a suit.

So, where does that leave people like me who are drawn to “they” but who want to be good allies?

-

I can rebel against the gender binary by normalizing all this and educating others (particularly other white, heterosexual, cisgendered men in power).

-

By default when referring to someone else whose pronouns I don’t know, I tend to use “they” nowadays.

-

I can name my pronouns (“he/him”) when I introduce myself and ask the other person for theirs.

-

I’ve also tried on stating my pronouns as “he/they” (i.e., “he/him or they/them”) sometimes.

-

I can refer to myself in my writing as a “white, cis, hetero guy” instead of leaving that unsaid (and thus unintentionally acting as if it’s the assumed default).

-

I can experiment with ways of embracing a little more femininity myself (or at least less “vanilla” masculinity), such as wearing scarves marketed toward women because of their less-muted colors…

-

…(Plus, while I’m not personally drawn to this—as of now, at least—some men also choose to experiment with make-up, jewelry, nail-painting, and other things that have traditionally been considered feminine.)

If you notice any emotional reaction reading that list, I invite you to examine: What’s going on there? What does it mean to you if, say, a male-presenting (i.e., male looking) person wears nail polish?

Really notice. What do you decide? That this person must be… gay? trans? Or perhaps, just not strictly “he” or “she”?

Wrapping up:

I believe that dismantling white supremacy benefits both people of color as well as white people.

Similarly, educating people about pronouns and normalizing their usage most benefits people who identify as trans, non-binary, or gender nonconforming.

But I believe it actually liberates all of us—even heterosexual cisgendered guys like me.

It makes all of us more free—to live as we are and as we want to be.

—

Thanks so much for reading this (and, if it resonated with you, please share it with other men in your life).

I’d love to hear from you:

What’s your biggest takeaway? What will you be left pondering?

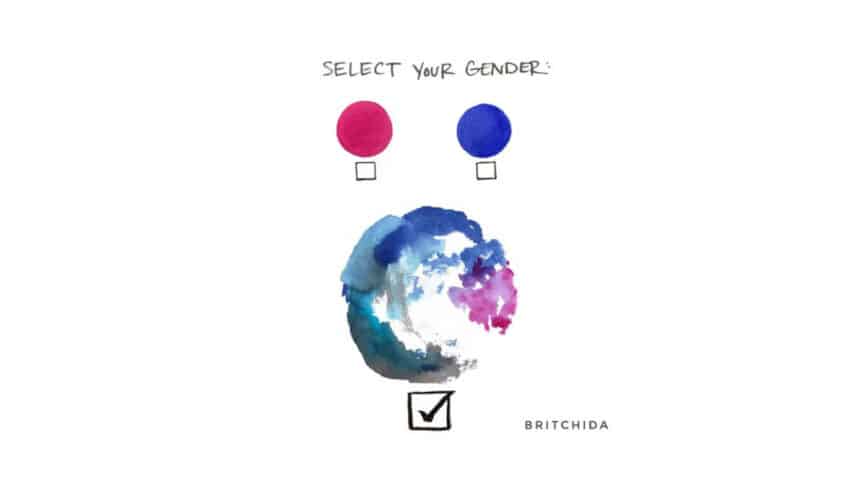

(P.S. The amazing piece of art I used for the cover image on this post is by Britchida. I didn’t ask for their permission to use it, but I love their art for simply conveying complex topics like gender, and I encourage you to support them and buy it.)

—

September 2024 Update:

I wrote this article two years ago. Since then, after a lot of internal work and additional investigation, my gender identity has continued to evolve.

An update:

I now list my pronouns as “they/he” (i.e., “they/them” primarily, but I won’t be at all offended by “he/him” either).

The main reason (aside from a general feeling of joy and increased safety when I spend time in queer-friendly spaces) is that I’ve continued to deeply examine the list of traits typically associated with femininity/masculinity.

The more I feel into it, the more I identify with the “feminine” ones, even though I’m masculine-presenting (i.e., I look male) and mostly heterosexual (i.e., I’m still only attracted—so far in my life, at least—to people who are feminine-presenting).

For example, I identify more with reflection over decisiveness, empathy over assertiveness, allowing over control, collaboration over self-reliance, interdependence over independence, etc. (If you’re curious, you can check out the comparison spreadsheet I made here: https://bit.ly/masc-fem-attributes.)

What about the “heterosexual” piece?

It’s tricky since I’ve had multiple partners now who identify as non-binary. Thus, logically, I can’t call myself fully heterosexual since that word implies a gender binary with only two choices (and that I’m one of those default genders attracted to people of the other default gender).

More precise terms for me might be “skoliosexual” (which indicates an attraction to non-binary people) or “femmesexual” (an attraction to women and feminine nonbinary people). But, since those terms aren’t very well known, I tend to refer to myself now as “mostly heterosexual.”

(By the way, reading those two new terms, you might have an immediate reaction that all this is getting out of hand—that terms like “femmesexual” just sound ridiculous. I’ve had that kind of reaction too, but I invite you to remember that gender is a social construct, and thus as culture changes, so too can its conception of gender. Thus, it’s actually a very natural process to come up with new, more precise words as we as a culture recognize gender expressions outside a strict binary.)

All this is just scratching the surface of a hugely complex topic. There’s so much more I could say about this, but for now, I’ll just add one last piece.

How this ties into personal growth:

When I coach someone, a lot of what we do together is examine the stories and rules that have been imposed on them—by parents, culture, media, etc.

Typically, those internalized beliefs are a huge part of what’s holding that person back from achieving their biggest dreams (e.g., “I need to be perfect,” “I’m not worthy,” “I don’t belong,” “I don’t deserve that,” “I’ll finally be happy once I have X,” “I shouldn’t complain,” “I’m not allowed to fully be myself,” etc.).

As I’ve gone deeper and deeper into my own exploration of gender, I’ve realized just how many of these kinds of beliefs and rules are tied to the gender we were assigned at birth and raised with.

For example, just because I’m male, does that mean I’m supposed to be the one who asks the other person out (or pays for dinner)? Am I supposed to be the chaser? Am I supposed to be the dominant one? Am I supposed to be the one who keeps my emotions in check while my partner cries on my shoulder? Am I supposed to be the more physically strong one who’s better able to do repairs around the house? Am I supposed to be more aloof and less needy?

No, I don’t think any of that is true—but those are lessons I’ve deeply internalized because I was raised in this dominant culture.

So, I increasingly believe that truly deep personal growth work must also include a very careful examination of what’s been imposed on us via gender, race, and a wide variety of other culturally-defined attributes.

Thanks for reading, and if you’d like support with exploring how any of this might apply to you, I invite you to apply for coaching.