This is post #3 in my COVID-19 series.

- #1 is here on general COVID info and precautions (somewhat outdated now)

- #2 is here on building a bubble/pod and navigating feelings, communication, and agreements (this info is still valid)

- #4 is here on the coronavirus variant discovered in the UK, the latest research-backed precautions, vaccines, and more

- #5 is here on how risk changes once you or your friends have been vaccinated (this info is still valid too)

First of all, I want to very much acknowledge how frustrating all of this is.

There’s so much work required just to live our lives right now. This is hard, and it’s normal to feel really stressed out.

Deciding how to think about COVID 7+ months in is incredibly confusing, especially if you live with other people. I’m about to start another community house with some new housemates, and it’s required an immense amount of time to research the latest science and to get everyone on board with the right balance of safety and freedom.

There’s so much complexity here, so I’ve done my best to assemble some of the best resources I’ve found to make this more approachable for others who don’t feel like devoting dozens of hours to it.

I feel lucky that a lot of smart people have put a great deal of effort into those resources. Thanks to them, we have additional options beyond just “give up and resign ourselves to getting COVID” or “never leave the house to stay absolutely safe.”

This doesn’t have to feel stifling. It’s possible to get both our safety and mental health needs met if we approach COVID risk management with intentionality.

In this post:

- Why this is important: It’s easy to lose track of why all this is important (especially if you’re young and healthy and none of your friends seem “at-risk”), so I’ll explain the three reasons I use to remind myself of why safety is still important.

- How your choices impact others: I’ll explain what I’ve learned about network epidemiology and how visiting “just one friend” is a bigger deal than it seems.

- How to do it: I live in a community house with 6 other people, so I’ll explain the best method we’ve come up with for navigating risk objectively in a science-based way that balances freedom/autonomy with safety.

Reading time:

17 minutes

A note on privilege:

The people in my house are able to afford to have these conversations. Communities of color and other marginalized populations have been hit a lot harder by the pandemic and might not have the luxury of limiting their exposure as I’ll be describing on this webpage. Many people who can’t work from home don’t have control over their work environments and are forced to take on more risk than they’re comfortable with.

Disclaimer:

I have no medical background. I’m simply someone who’s read a lot of articles and is skilled at summarizing and simplifying complex subjects.

First, why should you care about trying not to get COVID?

We’re all tired of this. It’s so, so easy at this point to just say “screw it” and do the bare minimum (e.g., wear a mask when grocery shopping because you have to) but then otherwise go back to a fairly normal lifestyle of being physically close to friends, eating dinner at other people’s houses, etc.

It’s very reasonable that you just want it all to end and for things to go back to how they were. All of this is hard.

It’s also easy to think that it’s either inevitable that you’ll just get it at some point, or that it probably won’t be a big deal for you. You might not even have anyone in your life who seems high-risk (maybe you only hang out with young people, for example).

When I find myself heading toward that “who cares” attitude, here are three reasons I use to remind myself about why it’s important to do what I can to avoid COVID (and no, that doesn’t mean hiding away with zero social contact—see the rest of this document for how to balance safety with living your life):

Reason #1: Protecting my long-term health:

We still don’t know the long-term consequences of contracting COVID-19.

Articles in highly-reputable sources like Mayo Clinic and the journal Nature have explored the potential long-term effects of COVID-19, including damage to the brain, heart, and lungs. Many people who have recovered from COVID-19 have also gone on to develop long-term conditions like chronic fatigue syndrome and more.

An August article in The Atlantic explored the tens of thousands of “COVID-19 Long-Haulers” who remained sick for months. These people had an average age of 44, and most were formerly fit and healthy.

Even if you do recover quickly, journalist Bill Plaschke described his COVID-19 experience like this: “It felt like my head was on fire. One night I sweated through five shirts. I shook so much from the chills I thought I chipped a tooth… I coughed so hard it felt like I broke a rib.”

Reason #2: Protecting my finances (and the finances of people in my life who have less money):

The reality of healthcare in this country is that the system is full of intentionally-hidden costs that add up very quickly, even if you have insurance. And for the 27 million people who don’t have insurance, their lives can be ruined by a single huge hospital bill.

If you get COVID, Time reports that treatment for someone with employer-provided health insurance and no complications averages nearly $10,000. If you experience complications, that number can double to over $20,000. The NY Times reports on another study that showed a median cost of $31,575, and, for patients over age 60, 25% had bills of nearly $200,000.

Reason #3: Protecting other people (especially frontline workers, at-risk people, and people from marginalized populations):

1 in 3 Black Americans knows someone who died of COVID.

Black Americans are dying from this disease at twice the rate of white Americans. This is not because of any genetic difference that makes them more susceptible. Rather, it’s because of structural racism in this country that has led to a wide variety of barriers for people of color around healthcare, nutrition, and other forms of support.

How much do you support the Black Lives Matter movement?

The wealth gap is also very much at play in terms of who is at risk of getting COVID. Many wealthier people have been able to dramatically reduce their risk by working from home this year. People who work in foodservice, healthcare, transportation, etc. have much less of a choice. They need to endure whatever conditions are in place where they work.

You might not even know any food service workers or nurses yourself. But they’re probably shopping at the same grocery store as you. You’re probably walking by them on the street. That friend you had dinner with last night might have some connection to one of those at-risk people. See the “network epidemiology” section below for more on how we’re all a lot more connected than it might appear.

In other words, just because you personally don’t know someone who seems at greater risk doesn’t mean you’re not connected to them or coming into contact with them (and yes, any one brief interaction at the grocery store, etc. might be low risk, but all those “low-risk” activities add up).

So, those are three major reasons why it’s important to stay strong and keep taking this seriously. Does at least one of them resonate with you?

The problem with risk management: It’s hard for us to assess what risk means

Most of the guides and images being passed around on social media will rate activities as “low risk,” “high risk,” etc. But what does that really mean?

Is driving a car “high risk”? What about the risk of negatively impacting our mental health? Being lonely has health consequences too, so just visiting one extra friend shouldn’t make too big a difference, right? And what if you actually get COVID? Only a small percentage of people actually die, right?

Clearly, we need a better way of thinking about this.

First, let’s talk about how connected we all are; then, I’ll describe how you might approach risk management.

Network epidemiology: Yes, visiting just “one more friend” makes a difference

Yes, there are absolutely very real negative consequences of being alone and missing out on social connections. That’s why finding ways to regularly connect with people is important.

One way of doing that is to be creative with finding ways to connect while staying safe. For example, the risk of transmission outdoors is quite low if you stay 6ft apart, even without a mask.

Another way is forming a proper bubble. But here’s the problem: A lot of people are using that term very lightly. The bubble has to be tight, and each additional person you connect with outside it makes a substantial difference.

Check it out in four images below (summarized and images from here, an article written by network epidemiologists at the University of Washington):

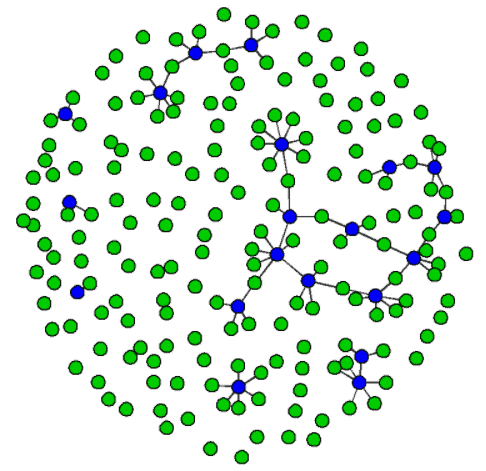

1) Here’s what a community of 200 households looked like pre-COVID (each green dot is a household and gray lines are connections): |

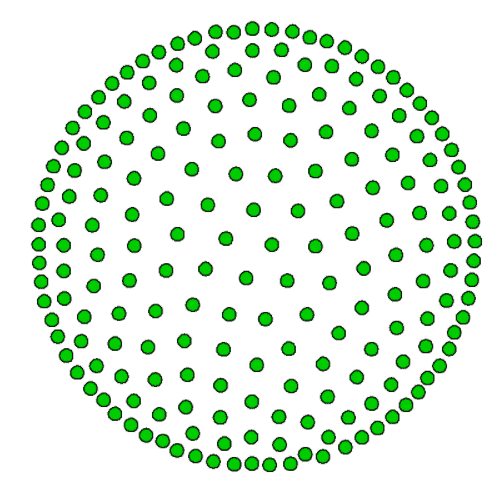

2) Here’s what it would look like if all the houses stayed completely isolated: |

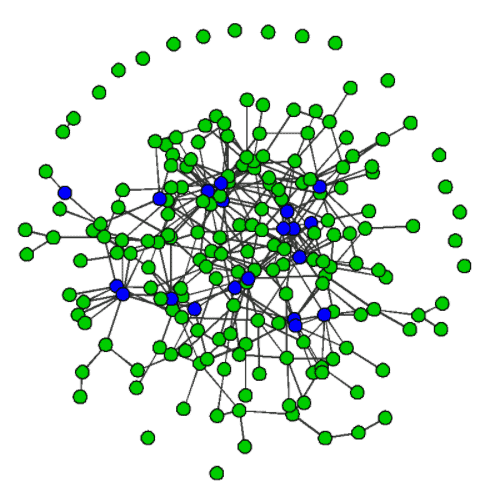

| 3) That would quickly eliminate the virus, but it’s impractical. We at least need some essential workers to keep our society functioning, so this image imagines that 1 in every 10 households has some kind of essential worker. Notice how this creates some connections between houses, and the largest cluster includes 53 households being connected (not intentionally, but simply through the interactions of those essential workers):

|

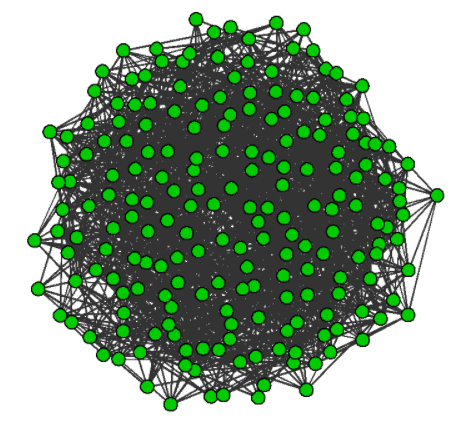

4) Here’s what happens if everyone visits just one friend in another household (avg. household = 2.6 people) without proper social distancing, mask-wearing, etc. Notice how the largest cluster is now connecting 181 households (91% of the total). So, think about how quickly the virus can travel if just one person gets it, even if they’re multiple household connections away from you:

|

In other words: Even if you’re just hanging out with one friend outside your bubble, unless they have zero contact with the outside world, you’re creating another pathway in that long cluster chain along which the virus can travel.

Of course, that particular connection in the chain becomes significantly flimsier if you follow proper protocols (see “specific practices” section at the bottom).

Here’s a simpler way to think about specific risk calculations: using the concept of microCOVIDs

The following is my summary of key points from the excellent whitepaper on the microCOVID calculator website. Again, all credit to them for making that amazingly thorough tool and writing that accompanying whitepaper. I’m summarizing the key points from it here (plus a few of my own interpretations) because it’s quite long and detailed, and it took me a while to really make sense of it. So hopefully this will help you.

Here are two reasons I recommend using a tool like this instead of just “feeling into” what seems right:

- Humans are easily biased. Our brains aren’t designed to do detailed statistical analyses. A computer is much better suited to that type of task. Plus, we’re so socially wired that we always want to make exceptions for people we like. Relying on an algorithm to help you make choices removes the burden from you of having to sort out what really makes sense and what might be your feelings clouding your judgment.

- The information is constantly changing. Unless you’re willing to keep reading the latest science articles as they come out, it’s much easier to just rely on a tool that’s using regularly-updated data to inform what it tells you is safe. For example, I wrote my previous COVID blog post at the end of August. Back then, the risk level where I live (according to Brown University’s excellent county-level tracker) was yellow. It’s now orange. Logically speaking, it makes sense to take different precautions with such a big jump in cases here. If you use the microCOVID calculator I recommend below, it will do all that for you automatically.

What is a microCOVID?

Let’s define 1 microCOVID as a one-in-a-million chance of getting COVID.

Using the microCOVID calculator, you can plug in different activities and see how many microCOVIDs of risk they represent. All the data is regularly updated and customized for your area.

For example, an activity that’s only 1 microCOVID—such as a 30-minute walk with a friend outside wearing masks and keeping 6ft apart— is extremely unlikely to transmit the virus and you can safely do it many times, whereas an activity that’s 3,000 microCOVIDs—such as a one-night stand with a random stranger—represents a very high degree of risk.

What is a reasonable “maximum % chance of getting COVID in a year” to aim to work within?

The creators of that calculator (who live in a community house together) decided that they were comfortable taking on 1% of individual risk of getting COVID.

In other words, they only allow themselves to do activities whose total point values together mean they’re never taking on more than a 1% risk of any one house member contracting COVID in a year.

Here are two reasons they settled on 1% as their preferred level of risk:

- Taking care of others: If everyone in the country kept to a 1% level of risk, the pandemic would remain manageable because it would spread slowly.

- Taking care of yourself: If you’re under age 40 and don’t have other risk factors, then accepting a 1% risk of getting COVID means that you have the same risk of long-term health consequences due to that disease as you would from a year of driving. In other words, the following (A and B) have the same likelihood:

- (A) Doing the set of activities that add up to a 1% risk —> getting COVID —> having long-term health consequences

- (B) Regular car driving for a year —> getting in a car crash —> having long-term health consequences from that

Remember that the danger of COVID isn’t just death. We still don’t fully understand how it works, and a study found that 1 in 10 who have had COVID were not fully recovered after 3 weeks. Even people who had been quite healthy beforehand have still been left with permanent lung damage.

Let’s work with 1% risk level for now as an easy clean number, but remember that the conditions are constantly changing around us, so we’re going to have to check the calculator to see what level of risk makes sense as things change over time.

- For example, 1% risk today might mean a fair amount of freedom to do various activities. But, if in a month from now there’s been an explosion of cases in this area, operating within that same 1% level of risk might mean much more tightly restricted activities since those same activities will now cost more points.

Ok, so what does that 1% risk level translate to in microCOVID points?

Because 1 microCOVID = a one-in-a-million chance of getting COVID, that means that a 1% risk (i.e., a one-in-a-hundred chance) would equal 10,000 microCOVIDs allowed per year.

- If you’re curious where that came from, think about two things: first, you know that 1 microCOVID = 1 / 1,000,000; second, you want to find how many microCOVIDs represent 1% risk, which is 1 / 100; so, you need to solve for X in the equation X / 1,000,000 = 1 / 100, which ends up as X = 10,000.

Ok, so if you were living alone, you would have 10,000 points to play with over a year to still fall within that 1% risk threshold.

But, let’s say you live with people or have some other kind of pod or bubble where you regularly interact with a group of people with close contact, no masks, not sanitizing objects that you both touch, etc.:

- If the people in your pod have absolutely zero contact with anyone else whatsoever (i.e., they literally never leave the house), then you’re good—10,000 points still.

- But, if they go for walks, go to the grocery store, etc., you need to account for the risk that they bring into your life. It might be small, but if you have 5 housemates and they all go to the grocery store once a week, those small bits of risk all add up.

- In short, it’s more important to think about the entire bubble’s level of risk rather than any one of its individuals.

What does all that mean right now?

According to the calculator, given current conditions in late October in Multnomah County, Portland and a 6-person household, the baseline risk of getting COVID from each other is around 800 microCOVIDS per month, which is 9,600 per year.

- (To find that on the calculator, set your location on the left, then set “number of people near you” to be the other people in your pod, then set “person risk profile” to be “in a closed pod,” then choose “type of interaction” to be household member. That’ll give you a weekly value, so multiply that by four to get the monthly cost in microCOVIDs of just living together without any additional activities.)

- Clarification on the concept of “baseline risk” based on a comment on this post: If I live alone, going to the grocery store represents X points of risk for me (i.e., contracting COVID from one of the other grocery store shoppers). If I live with 5 other people and each of us goes grocery shopping, I still need to account for that X points of risk myself, plus there’s now the additional risk of me getting COVID from my 5 housemates (since each of them has run the risk of getting it from one of the other grocery store shoppers on each of their grocery store visits).

So, if we subtract that from 10,000, you’re left with only 400 points for the year, which is 33 per month—not much room for activities outside the house.

Remember that the data in the calculator is updated regularly automatically, so this means that conditions are now worse than when the calculator was created and its creators decided that 1% risk (10,000 points) was reasonable for them. That makes sense since cases have been going up again (in fact, October 23 was our all-time high for new cases in Oregon).

What should we do then?

Two real options:

- Decide that conditions are now dangerous enough that you want to be very careful and spend only those 33 points per month (roughly two quick grocery store visits).

- Increase the risk threshold above 1% to get more points to work with.

#2 seems reasonable, but we have to be careful not to raise it too high. If we go with 1.5%, then we get 15,000 points per year. So if we subtract 9,600 hundred, we’re left with 5,400, or 450 per month.

What would that actually look like?

As an example for Portland in late October, here’s what would be possible at three different risk levels in a month (all based on the microCOVID calculator, and remember that this is just an example and you could instead allocate your points very differently, such as doing many more outdoor walks versus a single indoor dinner):

- Living in a house with 5 other people at 1% risk level (33 points per month to play with after subtracting out bubble baseline):

- 4 visits to the grocery store for 20 minutes wearing a surgical or N95 mask

- Living in a house with 5 other people at 1.5% risk level (450 points per month to play with after subtracting out bubble baseline):

- 4 visits to the grocery store for 30 minutes wearing a normal cloth mask

- 1 outdoor dinner for 2 hours with 2 people without masks at 6ft apart

- 4 outdoor walks with 1 person without masks at 3ft apart

- 1 outdoor lunch at a restaurant for 30 minutes with 5 people without masks at 3ft apart

- 1 indoor hangout for an hour with 2 people wearing masks at 3ft apart

- 1 indoor dinner for an hour with 2 people without masks at 6ft apart with windows open and a fan or air purifier on

- Living in a house with 5 other people at 2% risk level (867 points per month to play with after subtracting out bubble baseline):

- All of the above plus:

- 1 extra indoor dinner for half an hour with 2 people indoors without masks at 6ft apart and no windows open or air purifier

- 1 extra indoor hangout for an hour with 2 people wearing masks at 3ft apart

- 2 extra outdoor walks with 1 person without masks at 3ft apart

Here are some specific practices to reduce your risk

- Remember “MOD”: wear a mask, meet outdoors, keep your distance

- Masks:

- Earlier in the pandemic, researchers thought that masks were only about protecting other people from you. It’s now proven that they also help protect you from others.

- Type of mask is important: P100 respirator is best, followed by N95, followed by KN95 or 3-layered surgical mask, followed by a mask with a PM2.5 filter, followed by a cloth mask (a cloth mask is roughly half as safe as a surgical mask).

- Outdoors:

- Being outside with someone is roughly 20x safer than being inside, especially if you’re moving.

- Being in a larger room with someone is safer than a smaller room since the particles can spread out more.

- Ventilation is critical. Driving with all the windows open is only a little less safe than being outside. Being in a house can be made safer by opening windows, blowing fans, and using air purifiers (if they have HEPA filters and a high ACH value, which represents how often they filter all the air in a room).

- Distance:

- Being less than a foot apart is roughly double the risk of being 3ft apart.

- 3ft apart is roughly double the risk of being 6ft apart.

- 6ft apart is roughly double the risk of being 10ft apart.

- Risk level goes up roughly 5x if people nearby are singing, chanting, yelling, or breathing heavily (e.g., working out)

- Hand-holding and hugging are actually not as unsafe as you might think, as long as… for hand-holding, you’re careful to sanitize your hands, not touch your face, and not turn toward each other unless you’re wearing a mask; and, for hugging, you wear a mask or hold your breath, keep the hug short, face away from their face, and quickly move back to 6+ ft apart when you’re done

- Finally, remember that the amount of time spent with people is a critical factor. Even if you’re near someone for a couple of minutes without a mask, you’re unlikely to get COVID. But risk goes up over time and with repeated exposure. Walking outside with someone for a few hours is riskier than for half an hour, and meeting daily is riskier than once a week

- (More in my longer blog post about specific practices here)

Some other awesome resources:

- COVID: Can I do it?

- Exceptionalism and the Pandemic: Enacting Allyship through Social Distancing, by Leah Baker

- COVID Risk Levels by County

- A room, a bar and a classroom: how the coronavirus is spread through the air

Thanks for reading, and stay safe!