Summary: This is the first post in my Willpower series. I explain how habits work and how to change them based on the latest research in behavioral psychology.

My Willpower Series: This post offers an overview of the subject of behavior change. Part 2 focuses more on starting new habits and working on multiple changes at once.

Reading Time: 12 minutes

The most important resource in my life

I’m always interested to hear what superpower a person would choose.

Personally, I’d go with time travel. But if it’s a more junior-level genie giving out the powers, I’m choosing unlimited willpower—the ability to recharge my energy and self-control on demand.

Because more often than not, the problem isn’t that I’m not sure what I need to do next in life. It’s that I feel like I’ve run out of the willpower I need to force myself to take action—especially after a long day at work.

To me, willpower is the single most important resource in my life. When I feel it, I’m able to make progress toward my goals. When I don’t, I feel totally stuck.

Suiting up to fight your demon

Everyone has a secret demon they’re fighting—that force that they know is holding them back from what they want to do.

For most of my 20s, my demon was that I felt overwhelmed by all the different directions I could go with my life—I couldn’t decide what I wanted to be when I grew up.

Over the past few years, I feel like I’ve finally settled on a mission that’s important to me. And now that I know what I’m working toward, my new demon is energy—managing that limited pool of motivation I have each day to get my personal projects done.

So that’s why I decided to focus on the topic of willpower for my first few posts on this blog. To me, learning how to manage and recharge your willpower is the foundation of self-improvement. It does you no good to have an amazing personal development todo list if you can never actually implement any of it.

In this two-part series, I’m going to condense down the latest thinking from some of the most prominent experts in psychology, neuroscience, economics, and beyond. My sources include: Charles Duhigg (The Power of Habit), BJ Fogg (tiny habits), Stephen Guise (Mini Habits), Scott Adams (How to Fail at Almost Everything and Still Win Big), and Kelly McGonigal (The Willpower Instinct).

My hope is to package their ideas together and throw in examples from my own life to make the concepts as easy as possible to understand and apply yourself.

Sound good? Let’s get started.

Change is hard, but science is showing what works

Depending on the study you’re looking at, somewhere between 80-92% of New Year’s resolutions fail by February.

That’s why there’s an overwhelming number of articles out there today on how to achieve your goals. But, the good news is that the real science of behavioral change has been exploding. So let’s take a step back from all the “top 10 tricks” articles and start with the most consistent findings from all this new research.

Before we dive in, I’d like you to take away three things from that New Year’s statistic:

- Real, lasting habit change is hard. So don’t beat yourself up if you’ve failed in the past. Since only 8-20% of resolutions succeed, everyone else is failing too.

- It’s probably not enough to just “try harder” next time. If you want changes to stick, it’s important to understand how habit formation works. I’ve read all the books so you won’t have to, and I’m going to break down the specific processes that have been proven to work.

- If you want to change something in your life, don’t wait until New Year’s—or any particular date. Start right now.

How to change habits

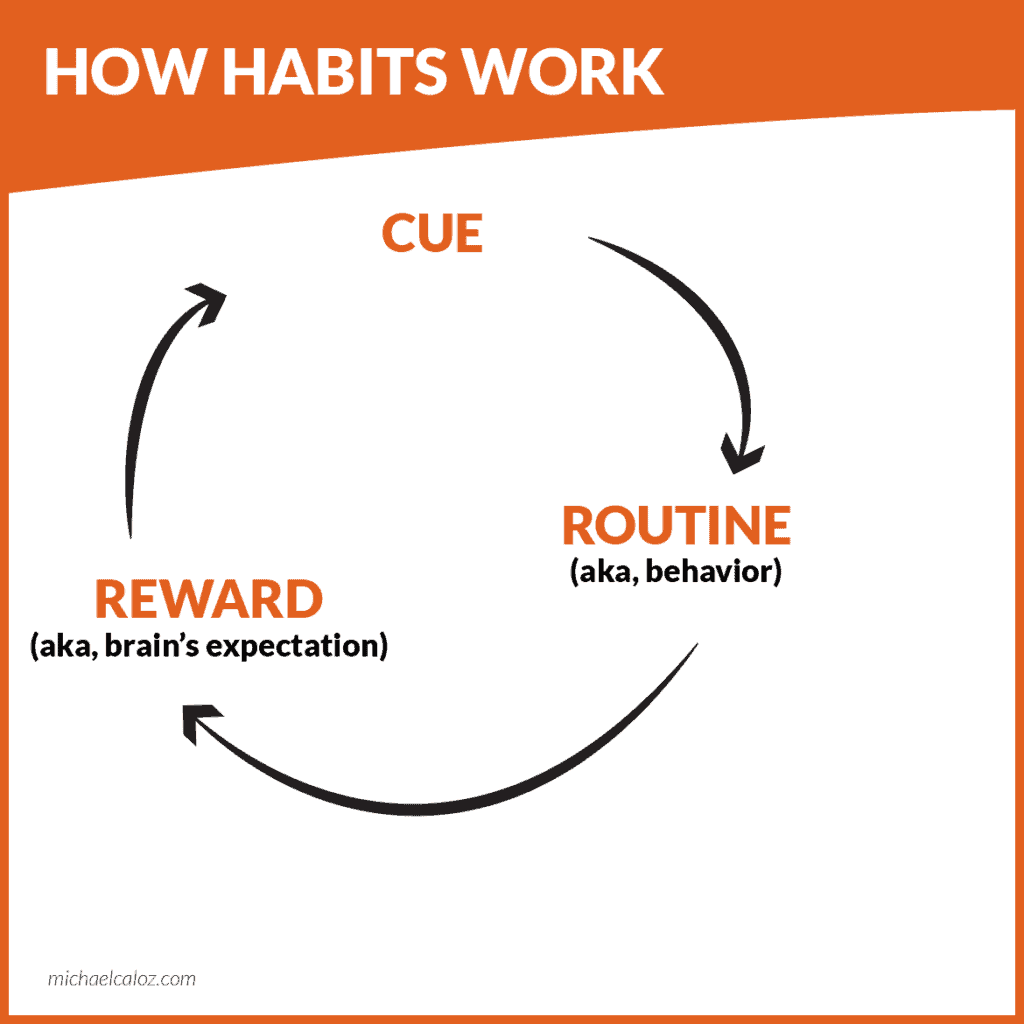

Charles’ Duhigg’s 2014 book The Power of Habit is the modern bible on the science of habit formation. In his research, Duhigg has found that what he calls the “cue-routine-reward loop” is the foundation of every habit.

- Cue: The thing that triggers a behavior

- Routine: The automatic behavior that you start doing when you experience the cue

- Reward: The pleasant thing you get for completing the routine (more specifically, the thing you’ve trained your brain to expect to receive after completing that behavior)

The cue-routine-reward loop

Here are four examples:

| Cue | Routine | Reward |

| Get home from work (walk in the door and put down your bag) | Get a beer from the fridge and drink it while checking Reddit on your phone | Feeling relaxed after a hard day of work |

| Feel lonely when you realize it’s almost the weekend and you don’t have plans | Open up social media and browse for a while | Feeling happy and connected if anyone mentions you |

| Your co-workers go outside for a smoke break | Follow them and smoke | Getting to take a break from work, and feeling belonging with your co-workers |

| Wake up in the morning and see workout clothes by the door | Go to the gym and exercise | Feeling accomplished and pumped up for the rest of the day |

Can you think of a habit that you’d like to change? What would be the cue, routine, and reward?

Introducing the “Golden Rule”

To successfully make that change stick, Duhigg recommends what he calls the Golden Rule: Leave the cue and reward the same, but change the routine.

The trick is to figure out two things:

- The specific cue that leads to that habit

- The specific reward your brain has been trained to receive for completing that habit

This can be tough when it seems like there’s an obvious answer but there’s actually more going on beneath the surface.

Take a look at the beer example in the table above (the first row). I wrote that the reward is feeling relaxed after a hard day at work; but, it could also have been enjoying the cold, refreshing feeling in your mouth. It won’t be the same for everyone—two people might drink that same beer for different rewards.

That’s one of the secrets behind Alcoholics Anonymous: They figure out what need the alcohol is fulfilling in the person’s life—a way to relax, an excuse to hang out with friends, a way to escape life’s hardships. Then, they provide similar relief through the group meetings. The AA member learns to ask for help when they experience their usual cue to drink. And by changing their routine, they’re able to get something close to their typical reward, but without the alcohol.

Last tip: If you have trouble figuring out the cue that’s leading to your behavior, try keeping a log each time you experience it—write down where you were, who you were with, what you’d been thinking about, what you’d been feeling, etc.

Your cue could be a location, a time, an emotional state, an action, or something else.

Try to be specific and figure out what was really going on for you—you might start with “hanging out with friends” but then remember the specific moment was when one of those friends made a joke at your expense and you felt like an outsider; so, the true cue was “feeling like I don’t belong.”

The practical way to replace your old behaviors

So, the trick is to replace the behavior you want to change with a new behavior that will lead to a similar reward. Then, you pair that new behavior with the old behavior’s cue.

Here are two examples from my life a few years ago. Looking back, I can see how I followed Duhigg’s Golden Rule without even realizing it:

(1) Goal: Drink less beer

Applying the Golden Rule: When I get home from work (cue), instead of “reach for that beer” (routine) to feel relaxed (reward), I tried “change into more comfortable lounge pants, then grab a cold kombucha” (routine) to feel relaxed (same reward).

Notice how I picked kombucha since it has a similar mouthfeel to beer, so that made the replacement even easier.

After some practice, I was able to try pairing two behaviors together:

(2) Goals: Start meditating, and get in shape

Applying the Golden Rule:

- When my alarm goes off in the morning (cue), instead of jumping into the shower (routine) to feel refreshed and awake (reward), get out of bed and immediately do 5 push-ups (routine) to get my blood flowing and feel awake (similar reward).

- Then, go straight into the shower (routine) to feel even more refreshed (similar reward, amplified).

- Finally, when I leave the bathroom (cue), immediately go to the couch and sit down to meditate for one minute (routine) to feel even more awake and refreshed (similar reward, further amplified).

The trick is to keep the same cue and reward but replace the old behavior with a new one.

If you’re not sure what exactly is driving your old behavior, try experimenting with different rewards.

For example, I run a lot of experiments on myself, and at one point I was trying to cut out coffee for a while to see if it affected my mood or energy. The problem was that I had a deeply ingrained habit of making myself a hot creamy latte every day when I got home from work (this was a few years after my beer phase 😆).

In this case, the cue and routine were obvious to me: “Walk in the door after work (cue) >> Make latte (routine).” But, I wasn’t 100% sure what part of the experience was the specific reward my brain craved. So, I tried a few different things:

- One day, I substituted another drink entirely: cold kombucha. It was better than nothing, but I didn’t feel satisfied.

- Another day, I substituted a french press coffee (no milk). That was closer to the mark but not as good as my latte.

- Finally, I tried hot chocolate made with frothed milk and sweetened with the same maple syrup I used in my lattes. Bam, that was what my brain wanted—not quite a coffee latte, but it turned out that the creamy sweetened milk taste and texture was what I really craved as my reward.

To successfully give up my lattes for a while, I had to keep the same cue (walk in the door) and reward (enjoy a warm frothy milky beverage), but I needed to adjust the routine by replacing the coffee ingredient with chocolate.

Breaking bad habits with mindfulness

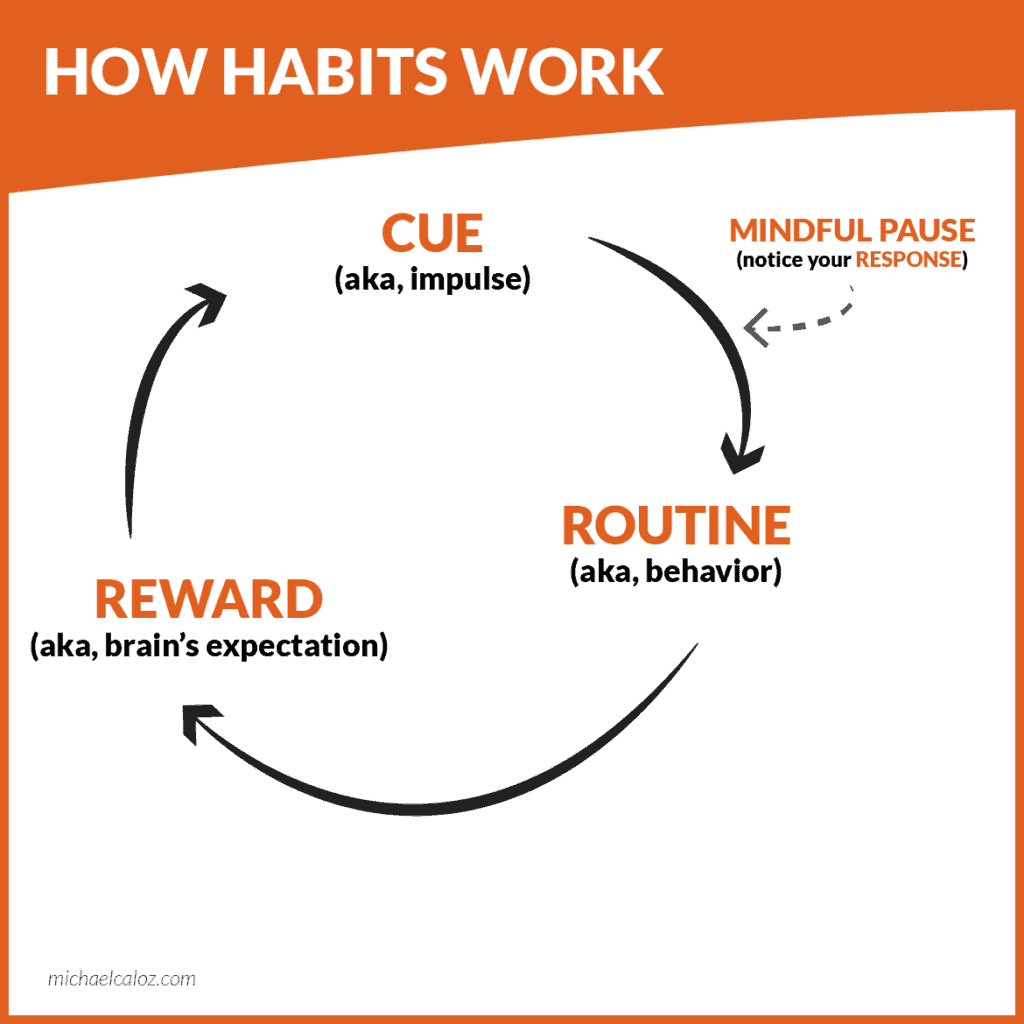

One more note about breaking bad habits specifically: In The Willpower Instinct, McGonigal suggests keeping an eye on what she calls the impulse and your response (very similar to the cue and routine but focused more on feelings).

Here’s how it works:

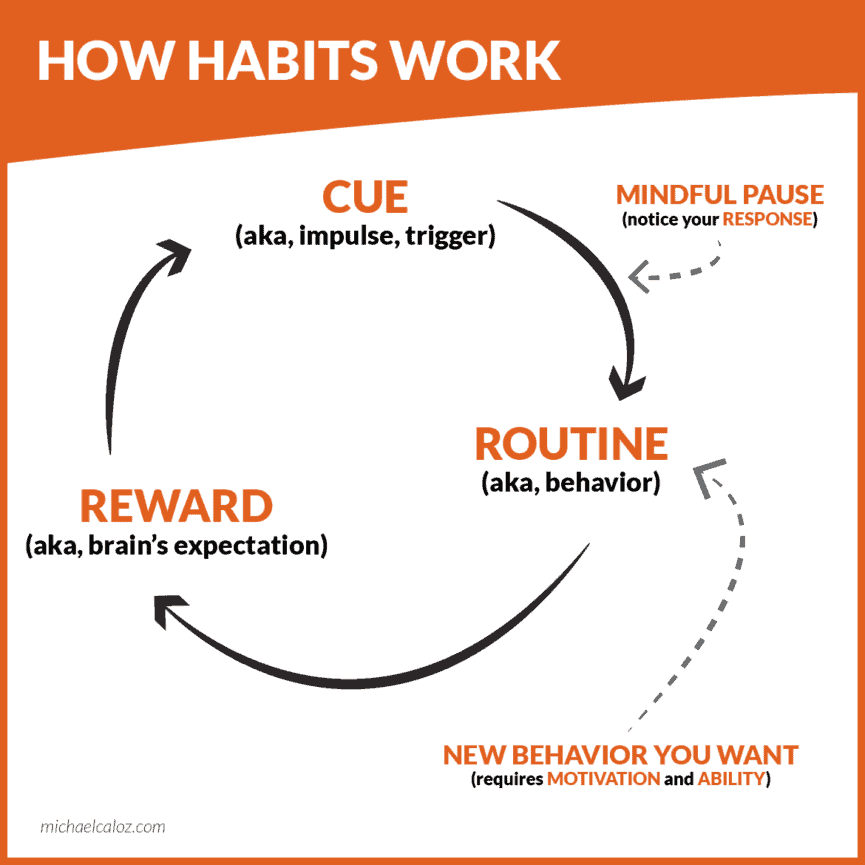

The cue-routine-reward loop plus the mindful pause

- Say you want to reduce your time on Facebook, but you feel the impulse to check it again.

- Stop to examine your internal response. How do you feel inside now? Then, once you’ve finished your Facebook time, do you feel better or worse? Did it actually make you feel good, or was your brain confused?

- Practice pausing and noticing—build a habit of noticing what you’re about to do, then stop for just a second before actually doing it. Say you’re swiping around on your phone and you realize you’re about to open Facebook without even thinking about it. Instead of tapping the app, try pausing for just a second so that completing that action becomes a conscious choice. This is a form of mindfulness, and research shows that it can be developed like a muscle. Best of all, that stronger muscle will help you out in any situation that involves self-control.

- At first, don’t try to change anything about your response to the impulse—just keep a record of how you felt before and after engaging in the habit.

- Over time, start to look for a pattern in your responses to the impulses that you’re interested in changing (“When do I find myself reaching for Facebook?”). Examine the specific types of situations that cause you to give in to temptation.

- Once you start to understand the cues, routines, and rewards at play, you can use the Golden Rule to change that habit (keep the cue and reward the same but change the routine).

Ok, but what if changing the routine is hard?

The 3 pieces you need to change your behavior

Dr. BJ Fogg is director of the Stanford Persuasive Technology Lab and one of the world’s top experts on human behavior change.

In his research, he found that 3 things are necessary to truly change a behavior: motivation, ability, and a trigger.

The trigger (very similar to the cue or impulse we’ve been talking about) is something that prompts you to take your action. For example, it could be hearing an alarm, arriving at a location (like the vending machine), or seeing a button (like the Buy button on a shopping website).

The interesting thing is that Fogg found that the trigger can only succeed if you have sufficient motivation (you want to do it) and ability (you’re capable of doing it). Motivation and ability are related too—if you have very high motivation, you might be able to achieve your behavior with less ability. And if you have very high ability, you might be able to perform the behavior with less motivation.

In other words, if you really want it, you can probably make it work even if it’s hard. And if it’s easy for you, you won’t need to push yourself as much to get it done.

Here’s how to put that into practice: Let’s say you want to improve your posture.

- Motivation: Be very specific about your goal so that you can tie the new behavior back to your motivation. For example: “Practice proper posture so I can feel more confident and develop the ability to walk into a room feeling like people want to talk to me.”

- Ability: Make it as easy as possible by breaking the behavior down into pieces. For example: “When I’m standing, keep my knees slightly bent and tuck in my stomach.”

- Trigger: Pick either a natural trigger to pair it with, or design one yourself. For example: “Whenever I walk by a mirror, take a quick look at my posture.”

One more trick is what Fogg calls “tiny habits”: Pick a behavior that you do every day that requires little effort and takes less than 30 seconds. Then, pair your new tiny behavior with an “anchor” trigger:

- After I get home from grocery shopping, I will cut up an apple for work tomorrow.

- After I get home from work, I will put my gym clothes by the door.

- After I get out of bed in the morning, I will meditate for 30 seconds.

Be careful: You should have a specific motivation in mind to inspire you—”become healthier so I feel more energetic,” or “become more mindful so I reduce my anxiety.” But the point here is not to name a specific success state like “lose 20 pounds,” or “reach enlightenment.” Instead, you should aim to define a system that you can keep doing.

That’s what Scott Adams’ book How to Fail at Almost Everything and Still Win Big is all about. If you make your goal “finish a marathon,” you risk feeling stuck or aimless once you achieve that. But, if your goal is “run 30 minutes every day,” it becomes easier to keep going even after you hit a milestone.

Be careful of these common problems

Don’t reward yourself too early

As you get started with creating new habits, there’s a fine line to tread between (1) giving yourself credit for taking the small action to get started, and (2) feeling so satisfied that you stop there without doing more.

There’s a common trap that I’ve fallen into:

- You decide you’re going to set an ambitious new goal for yourself—say, writing a book.

- You’re excited, so you start telling friends and family that you’re working on a book, and they reward you by telling you you’re awesome.

- When you hear all that praise, your brain gets flooded with happy chemicals.

The only problem is: You haven’t really earned it yet. And even worse: Once you’ve told your story enough, you might start to feel an uncomfortable mix of feelings—you’re excited to have people’s admiration, but you feel a bit like an impostor.

So, that’s why I’ve made a rule for myself: I don’t tell people about my new projects until I’ve made some actual progress. For example, I kept this blog a secret until I’d released my first post (which was especially hard for me since I usually like to get feedback from people I trust before releasing to the world).

To be fair, if you’ve been indecisive for a while, I do think that finally deciding to take action is impressive. I’d been thinking about it for years, so the moment when I really committed to starting my blog was a big deal to me, and it felt a bit anticlimactic that I was only allowed to experience that event alone.

But I also felt energized by that decision, and it inspired me to get started so that I’d have something real to show off to the people who are important to me.

Finding the inspiration to keep at it

Almost done. If you’ve decided to keep your project a secret as I suggested, here are two things that helped me when I was feeling alone:

(1) Surround yourself with like-minded people

I’d been going back and forth on starting my blog, but what really gave me the push I needed was putting myself in an inspiring environment and surrounding myself by people who had done something similar before.

The Forefront conference I attended was exactly what I needed. I was able to talk with real people who had done what I was thinking about, and meeting them in person really helped me see that they weren’t so different from me.

(2) Keep your specific motivation in mind

Even though I wasn’t sure exactly what my blog would end up focusing on, I knew I wanted to coach people on personal development and help them achieve their potential. That was my motivation. And to do that, I knew that I would need to develop a point of view on key topics and to get my name out there. So, creating a blog made sense as a foundational step for both those goals.

Making a change takes more than just information

I want to leave you with one more thought—something that I have to keep reminding myself because it’s so easy to forget.

I’ve always loved giving people advice, but it hasn’t worked out every time because real change involves more than just information. And that applies whether you’re working on a habit yourself or trying to encourage someone else to make a change.

Have a friend who smokes? It’s easy to imagine that all you have to do is prove how damaging it is to their health. Surely with the data in hand they’ll change their behavior, right?

It’s particularly tempting when it’s a topic that seems intuitive to me—for example, investing money in stocks instead of keeping it locked away in a low-interest checking account.

It can also be challenging if you’re a very logic-oriented person dealing with someone who’s much more feelings-oriented. You find yourself frustrated that they don’t just see your rational points and make the change that will “obviously” help them.

But to see why that line of thinking is wrong, all you have to do is look at yourself. Have you achieved all your goals already? Or is there a habit you’ve been trying to adopt for months or years, and it still hasn’t stuck despite everything you’ve read on the subject?

Putting everything together to take action

So what’s missing if it’s not just more information?

The answer is strengthening your willpower and building habits based on the principles of behavioral change that I’ve covered in this post. If you’re trying to help yourself or someone else change a behavior, it’s not enough to just know why the new behavior will be useful.

Instead, you have to link it to a specific goal that’s important to you (the motivation), shrink it down into something that’s actually doable (the ability), and follow the Golden Rule to pair that behavior with a strong cue and reward, ideally by replacing or adding on to an existing behavior (the routine).

At the same time, work that self-control muscle by practicing pausing and noticing before taking action. Finally, avoid rewarding yourself until you’ve made real progress.

The full cue-routine-reward loop plus the mindful pause and new behavior

So that’s it. Although each researcher uses slightly different words for some of these concepts, all the latest research on habits and behavioral change comes down this: Be more mindful about the specific trigger that causes a behavior, keep your specific motivation in mind, and understand what your brain expects as the reward.

By mastering that loop, you can understand how your current bad habits work and how to replace them with better ones.

That’s part 1 of my willpower series. In part 2, I dive into how to build multiple new habits at once and how to hack your brain to deepen the reserve of willpower that you draw from throughout the day.

Thanks so much for reading, and I’d love to hear from you in the comments. Which part of this resonated most with you? Do you have a new habit that you’re excited to build?